LARA GÜNEY ÖZLEN

Declaring Kaos GL magazine as obscene for various reasons in 2000 and 2006, the Committee for the Protection of Minors from Sexually Explicit Materials has also declared 8 children’s books as obscene since October 2019, limiting their promotion or deciding that they should be sold in sealed envelopes. The reason for declaring those publications obscene was explained as “existence of violence, extremism in gender discrimination and the promotion of transsexuality for children” in those books.

In March 2020, a lawsuit was filed against the translator of the books Declaration of the Rights of the Girls, Declaration of the Rights of the Boys which were declared obscene in October 2019, on charges of “mediating the dissemination of obscene publications.” The Union of Translators published a statement demanding that such practices, which make it difficult to practice the translation profession, should be ended. In addition to these, Buket Uzuner’s book The Most Naked Day of the Month, which was first published 34 years ago, and Ersan Pekin’s book These Women Eated Me Up were found obscene, their promotion was limited and they were sold with the tag “+18.”

We talked about this censorship process and what can be done against censorship with Kaos GL General Coordinator Umut Güner, who was the Editor-in-Chief of Kaos GL Magazine at the time it was censored, and with Hayriye Kara, the lawyer of the Kaos GL Association.

Kaos GL Magazine was offered for sale in a sealed envelope from the end of 2000 to 2002. Could you please tell us about this process briefly?

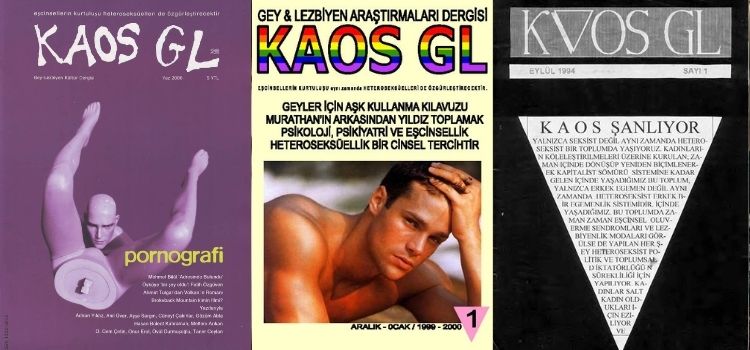

Umut Güner: Actually, at the end of 1999 the government noticed Kaos GL Magazine which had been being published since 1994, and said, “since you publish a periodical, you have to register it.” When we registered it, the state mechanism started to shape the publication with its own norms.

Thus, at the end of 1999, the magazine began to be published as a registered magazine on the Press Prosecutor’s Office. Due to a drawing made to raise awareness about HIV in our first issue (issue 63) that we published as a registered magazine, Kaos GL magazine started to be sold in a sealed envelope as a result of a decision by the Prime Ministry Committee of Protection of Minors from Sexually Explicit Materials in 2000.

Reading the communiqué we received, we understood that the decision was binding on all Kaos GL magazines and that Kaos GL magazine should be sold in envelopes from now on. For this reason, we thought that we should sell all the issues in a sealed envelope until 2002. Therefore, upon this decision of the Committee, the magazine was sold in envelopes from the 63rd to the 73rd issue. However, as a result of the response given in 2002 to our objection to this decision, we learned that it was decided that only the ‘related issue containing the HIV drawing’ would be sold in an envelope. Because of this confusion, it was as if we had “enveloped ourselves and censored ourselves” for a while. In this period, black plastic bags were used for selling magazines that contains pornographic content. As Kaos GL, we did not accept this plastic bag option and put the magazine in a yellow envelope.

Umut Güner

Regarding this issue, Ali Erol from Kaos GL wrote at the time that “if our association had a lawyer, we could have deciphered the legal meaning of this decision and not censored ourselves.” What do you think?

Umut Güner: It is clear that we need a lawyer not only to deal with the appeal process of Kaos GL Magazine, but also to understand the decision that was ‘notified’ to us. As I said at the beginning of the interview, when we received a response to our objection, we learned that we were censoring ourselves actually.

In the same period, the Library of Parliament requested that Kaos GL Magazine be sent to them. In other words, while Kaos GL was a magazine that “must be in the envelope” for the Committee of Obscenity, it was also a publication that the Library of Parliament wanted to put on its shelves for the benefit of lawmakers and parliamentary staff.

In 2006, you released the issue of Visuality of Sexuality, Sexuality of Visuality: Pornography, which was later ordered to be confiscated. How did you decide to publish this issue?

Umut Güner: Our desire to discuss the issue of pornography actually stemmed from the fact that the feminist movement in Turkey was positioned directly in an ‘anti-pornography’ position at that time. What does pornography mean for LGBTI+s? Is it that much of a ‘disgrace’ issue? Or is there alternative porn without the sexual exploitation mentioned and criticized? Can we make paralle”lities and similar claims about the porn industry in the LGBTI+ field and the porn industry produced for the heterosexual world ? This issue was an effort to find answers to such questions. This effort continued to be on the agenda of the movement from time to time.

“WE BOWDLERIZED THE IMAGES OF THE PENIS AND THE VAGINA”

While preparing the pornography issue, did you think that there would be a similar process to the previous one, taking into account the censorship you encountered in the 2000s? If so, did you self-censor while issuing the magazine?

Umut Güner: I cannot answer this question as “no, we did not think about it”. Because while we were preparing an LGBTI+ magazine that deals with pornography, we tried to be ‘careful’ even when we were selecting the visuals. For example, we bowdlerized penises and vaginas. Naturally, we thought that the measures we took would be sufficient. We knew that no matter what precautions we took, any production or content related to the LGBTI+ field was at risk of being found obscene and pornographic. However, the image in question, which caused the confiscation, is a photo of work of art. We did not think that the magazine would be prosecuted for having pornographic content over this work of art.

As the editorial board, we make a final check of the magazine when it comes back from the design department. As we evaluated the magazine in general, we talked about the picture of Taner Ceylan in his article – which then became the subject of the lawsuit. However, we continued thinking that this would not be a problem, as many publications on the market had similar content in the same period. We later presented these contents, which were published in the market during this period, in the case file. The most important difference of this visual from similar content was that this image was a work of art.

Could you tell us about the process leading up to the decision of the magazine to be confiscated in 2006 and the decision of the European Court of Human Rights regarding the violation of freedom of expression?

Could you tell us about the process leading up to the decision of the magazine to be confiscated in 2006 and the decision of the European Court of Human Rights regarding the violation of freedom of expression?

Atty. Hayriye Kara: Three copies of Kaos GL Magazine’s 28th issue were seized by the Ankara Public Prosecutor on 21 July 2006, based on Article 25 of the Press Law before it was published. On the same day, based on Article 28 of the Constitution and Article 162 of the Criminal Procedure Code, Ankara Public Prosecutor applied to the Ankara Criminal Court of Peace to decide on the seizure of all copies of the 28th issue of Kaos GL magazine before it was published. This request was accepted and all copies of this issue were confiscated. The Criminal Court of Peace has concluded that the content of some articles and pictures published within the framework of the ‘pornography’ file of this issue is contrary to the principle of protecting public moralty. An appeal was filed against this decision at the Ankara Criminal Court of First Instance, but the objection was rejected.

Following the rejection of the objection, an application was made to the European Court of Human Rights in 2007. 9 years later, the ECHR decided in 2016 that the freedom of expression had been violated. The ECHR underlined that the examination of the issue of general morality would be carried out more soundly by the local courts, because the society of each state is better known by the judges of that state. However, the Court justified the violation decision as follows:

“However, in the concrete case, with reference to the decisions of the local courts, it is not possible to determine which article or which image in the related issue of the magazine harmed public morals, for what reason. In fact, the decision of the Criminal Court of Peace to confiscate does not contain any element to be considered that the judge took care to examine in detail the compliance of the content of the magazine with the principle of protection of public moralty. The Criminal Court of Peace does not explain which article or which image in this issue of the magazine is against general morality. The decision of the Criminal Court of First Instance, which rejected the objection made by the applicant against the confiscation decision, does not contain any details or justifications in this regard. Therefore, the argument that the national judge had duly examined the criteria that had to be taken into account before limiting the applicant’s freedom of expression cannot be accepted, as the decisions rendered were not justified. The Court therefore considers that the justification that is too general and brought forward unreasoningly for the protection of morality is not sufficient to justify the confiscation and seizure of all copies of issue 28 of the magazine for more than five years.

Beyond this conclusion, by examining the issue in question personally, the Court finds that, when evaluated as a whole, the aforementioned issue of the magazine deals with the issue of pornography through critical and analytical articles, according to different approaches and especially the approaches of LGBT people. The Court observes that the issue in question also contained several explicit pictures, in particular one published on page 15, showing the sexual act of two men, both of whom represented the artist himself. The Court considers that these images, in particular the image in question, despite its intellectual and artistic character, can be considered as damaging to the sensibility of a society that does not have knowledge about this. According to the Court, considering the content of the articles dealing with the sexuality of the LGBT community and the explicit nature of some of the images used, the 28th issue of the magazine can be considered as a specific publication targeting a certain segment of the society. Taking into consideration the abovementioned issues, the Court considers that the magazine in question was not suitable for the whole society and, on the other hand, the applicant accepted this situation. The Court therefore recognizes that even if only a small fraction of the copies of the magazine are intended for sale on newsstands, the measures taken to prevent access to this publication by certain groups of individuals, particularly minors, may correspond to a requisite social need.

Atty. Hayriye Kaya

“LOCAL AUTHORITIES HAVE NOT TRIED TO IMPLEMENT LIGHT PREVENTIVE MEASURES.”

The Court reminds, however, that the nature and severity of the penalties imposed are also factors to be taken into account when assessing the proportionality of the interference. Although in the present case the necessity to protect the sensitivity of a segment of society, especially minors, was acceptable for the protection of public morality, The Court considers that it is not justified to prevent the entire society from accessing the issue of the journal which is a matter of dispute. In this context, the Court emphasizes that the local authorities did not try to impose a softer preventative measure than the seizure of all copies of the issue in order to prevent a public that does not have knowledge from accessing the magazine in question. Implementation of such a measure is possible, for example, in the form of an obligation to sell the magazine in a special packaging containing a prohibition of sale to those under the age of 18 or a warning for the persons under the age of 18, not in the form of confiscating the copies for subscribers, or even to somehow withdraw this publication from kiosks. As the decision of the Ankara Criminal Court of First Instance dated 28 February 2007 suggests, even assuming that the publication of the confiscated issue with a warning for those under the age of 18 was possible after the return of the seized copies at the end of the criminal case against the editor-in-chief of the magazine, that is, after the Supreme Court decision of 29 February 2012, the Court considers that the seizure of copies of the magazine and the delay of five years and seven months in its publication cannot be considered proportionate to the aim pursued.”

Umut, as the editor-in-chief of the magazine at that time, a lawsuit was filed against you in 2006. Could you please tell us about this?

Umut Güner: When the magazines were delivered to Kaos GL Association by the printing house, all copies of the magazines were confiscated by the decision of the Public Prosecutor. The Public Prosecutor’s Office invited me to the prosecutor’s office as I was the responsible editor-in-chief of the magazine. They asked us to share with them the address of the owner of the article and the photograph (we had to explain throughout the trial that the image in Taner Ceylan’s article is not a photograph and is a painting). We said that he is a famous painter, that they can reach him if they want, and we did not convey his address information. Thereupon, a lawsuit was filed against me because I was the Editor-in-Chief of Kaos GL Magazine.

Atty. Hayriye Kara: Ankara Public Prosecutor filed a public lawsuit against Umut Güner for spreading obscene images. The Ankara Public Prosecutor concluded that “the picture published on page 15 of the 28th issue of the magazine is clearly obscene and pornographic and does not require an expert examination”. However, according to the law, works of art are excluded for obscene content, so an expert examination is required to determine whether the contents are works of art.

In the end, the Criminal Court of First Instance decided to acquit Umut Güner. Because although the court accepted that “there was obscene content, all the elements of the crime were not formed since all the issues of the magazine were confiscated before it was published”. This decision was also upheld by the Supreme Court. However, the ECHR found no violation here.

“EVERY CENSORSHIP CASE NEEDS TO BE CAMPAIGNED”

Considering that many children’s books have been banned or age restrictions have been imposed on books recently, what do you think can be done against the Committee for the Protection of Minors from Sexually Explicit Materials and this wave of censorship that will likely continue?

Umut Güner: Basically, there are the standards brought by the state regarding publishing and you are expected to publish within this framework. They themselves already legally create a pattern of conformity and present a limiting framework. I think that the prohibition of publications and children’s books is not on the agenda of the human rights movement sufficiently. For example, the process after the ban decision could have been effectively monitored. Each ban and censorship case must be campaigned separately.

Exactly these days, there is an attempt to impose restrictions on social media on the internet. It is being discussed whether the social media users will be allowed to remain anonymous. This itself will actually be a process that directly restricts the freedom of internet users who want to use their freedom of expression anonymously. At the same time, it will be a process that will operate restrictive and self-censorship mechanisms for those who want to produce on the internet. As long as there is no hate speech, we should open spaces where each other can express their views and discuss. Basically, we can allow opinions that are unlike our own to appear in our own media.

“LGBTI+ ARTISTS CREAT MORE WORKS WITH THEIR OPEN IDENTITIES”

How do you observe the change that has taken place since the 2000s in terms of both increasing pressure on associations by the authorities and increasing censorship cases along with normalization of self-censorship?

Umut Güner: After the mid-2000s, the LGBTI+ movement started to gain strength and the scope and movement area of the LGBTI+ began to expand. However, at the same time, we are going through a period in which the current government is increasing its pressure. Especially the pressures in the field of freedom of thought, expression and association are increasing. Naturally, while we are going through a period when we feel strong and not alone, on the other hand, we live in a period when our freedoms are being restricted and we experience pressure more intensely. We are experiencing this ebb and flow intensely, and it creates tension.

At the same time, we are going through a period where LGBTI+ artists are producing more works with their open identities. However, I do not know how these production processes are affected by the current pressures. After all, I think self-censorship may not always be a conscious process, it may be reflected in productions spontaneously. An artist, organization, publisher, editorial board may need to step away from that process in order to look back on their production processes. However, I think I can say this: While in the past, the government and political actors could be criticized more easily, now we feel obliged to pay attention to every sentence we make.

Kaos GL is concerned about both protecting its own organizational structure and strengthening LGBTI+ organizations against oppression. The less injured we come out of the current process as LGBTI+ organizations, the less its reflections on the LGBTI+ community will be.