ERKUT TOKMAN

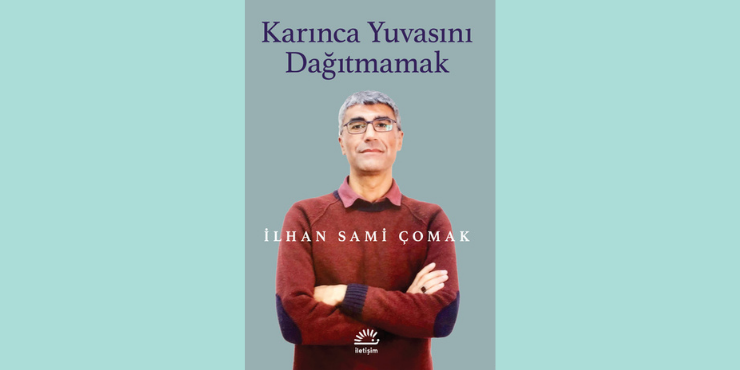

You all know İlhan Sami Çomak more or less now. Unfortunately, it is a well-known fact that İlhan Sami Çomak’s just cause has been ignored by the public for many years and left him alone. We can understand this most concretely from the fact that there is no serious and broad participation freedom campaign about him in Turkey. It has been 27 years since he was legally marginalized because of his Kurdish identity, deprived of his freedom, imprisoned, and his life stolen through the method of illegalization. As a Kurdish citizen whose conviction or detention has not yet been clarified, İlhan Sami Çomak continues to achieve an unprecedented miracle of humanity within four walls despite all unjust accusations, trials with uncertain evidence, torture, etc. he has been subjected to, during the years he spent in prison. Why? Not choosing the easy path which are hatred, anger, grudge and violence; but by taking poetry primarily as a guide, choosing the way of wisdom and enlightenment, the way of goodness, beauty, love and being a better person – humanization, it teaches us a great humanity lesson that will be rare, perhaps never to be found. I discovered this while reading the poetry books from the Yasakmeyve poetry series when I first contacted him. It is my principle to read and meet every poet I love. I felt this feeling after Enver Ercan gifted me İlhan Sami Çomak’s poetry books to read. Although I was working on the “writers committee in prison” at that time, we first met him through poetry. For this, I first contacted her sister Suna, then I got the address of the prison and wrote him a letter. Later, when I read the lines he wrote to me in our various correspondences, I understood once again: His humanity was so real, friendly, pure and sincere that he could not have been capable of committing any legal crime. But when I read his autobiographical book, Not to Destroy the Ant’s Nest, which was recently published by İletişim Publishing House, I understood this much better once again; because I had the chance to see and grasp the truth in all its nakedness, by reading İlhan’s own sentences, more concretely beyond feelings.

For me, this book is the book of İlhan’s re-embrace with himself and his world, and I am sure that this warm embrace – whether it is the first time or not – will be more or less the same for everyone who reads this book. Why? Because inside this book lies a huge, even giant, person whose heart is still beating strongly. This giant heart calls out to us from its own sincere world with the warmth and sincerity that emerges through the book as you read it, and opens the doors of its own reality to us with all its nakedness. In Theodor Roethke’s poem “Open House”, he says “My heart keeps open house, My doors are widely swung.” In this book, İlhan opens the doors of this house to us with all the nakedness of his heart. This warmth and sincerely cast reality is not a reality that can easily come out of our hearts and minds. It is so in many respects because behind the reality of a great Turkey lies the social, cultural, ethnic, legal and political realities that have been going on for decades. İlhan Sami Çomak is just another victim of long-standing and unchanging misstructuring in this conjuncture, and perhaps the worst example of our wounded, painful and bleeding reality. This is a reality that every citizen should lament for, be sorry for, and even rebel against. A determination of Kemal Şahin in the closing article of the book is the fact that it is already time for society and the judiciary to change, before it is too late, before other innocent people suffer this trouble again and again, and despite everything, he determines that it is still not too late with a positive outlook. The reality in the book contains many bittersweet fragments from all the realities of life, things experienced and the ones not experienced, hopes and regrets, happiness and pain, deaths and births, love and sadness, blood and tears… everything about life is in it.

Judging by the main factors that brought the book into being it should be said that it is very meaningful in terms of revealing the true story of İlhan Sami Çomak’s unjust detention for years, İlhan Sami Çomak’s struggle to survive and hold on to life, the change he went through in this period, his intellectual and spiritual evolution, what he witnessed, what he experienced… and many elements and stages (childhood, youth and maturity) of his own life journey from the poet’s own pen. In the poet’s own words, this language adventure, which started from his childhood years, which never let him down, the existence of Turkish language, which he faced in his primary school years, that he always failed in the classroom, identical with beating, learned from fear and fear of humiliation, namely that “Wall of language;” have turned into a great opportunity and miracle for İlhan today, by being cast by the impossibilities between four walls with his supreme effort, determination and discipline; the language of “poetry”, which is the most difficult one, thus its own “poetry”. See how the poet describes this freedom: “Poetry gave me the freedom to make mistakes. The unregular aspect of the poem led me to release my fear, to catch my limits with my feelings, my talent and determination to work, thus proving my strength” (p.31). Later in the book, we witness his years when he went out of the village life for the first time and met the state; for the first time, the school and youth years in “Bingöl”, where he felt that he had grown out of his childhood: “I grew up when I saw the State!”/”But I grew up in a very isolated area. I still can’t get used to it” (p.25). Witnessing the short time he passed at the university in Istanbul from here, taking into account his detention process, we find ourselves in a wide process in the book, which includes the chapters in which he talks about the dramatic processes he lived through and was exposed to during his prison years, and the adventure of being a poet in prison.

While witnessing all these processes written by the author; we are not just stepping into his physical, familial, educational and environmental world. At the same time, by looking again at what happened in all lived or not-lived time periods in the poet’s life (by not-lived I mean the period in the prison, and here I specifically mean the physical isolation from the outside world), who passed through and cast by the rememberances and the memory during these processes, we witness that he creates a brand new life experience and reality out of impossibilities and absences, by thinking about it, producing, questioning, seeking answers, and drawing conclusions. In this process, we get clues from a field of creativity and imagination that the author visualizes in order to create his own reality. So what contains this reality? Or we can also ask as follows: What does this reality offer us, the reader? What kind of life experience do we think about the realities of this society and the individual, by considering what has happened? I think that if we answer this based on the concrete facts presented to us by the book and its author, we will have stepped on a more correct ground: This ground is, of course, first of all, the climate and soil of the village where the author spent his early childhood years, where he was very happy with his family and village environment despite all kinds of absences, where he grew up. “My relationship with him was like a prayer,” he said; it is the willow tree whose body makes him feel the warmth of his skin by climbing up to kiss and smell it; it is the rivers of his uncle that are offended and flowing backwards, it is Khidr, whom he put in the place of God, the first holiness for him; are the fields where he grazes his animals, shepherd’s nomadicity, maybe it is the love of mother, father, brother and kin that will not replace any love for him, is the peace he feels when he rests his head in his grandfather’s lap, advice given by his grandmother… Again on this ground, the mischief of his childhood years, the sense of curiosity and discovery, the feeling of sharing purity, unconditional absence and poverty, Keke’s deep love, with the excitement of high school and early youth, getting to know life, coming face to face with religious, ethnic and cultural realities, recognizing the reality of the state and language, and the disappointments, marginalization, acceptance and rejections experienced as a result of these in Bingöl; and İstanbul the first city where he felt his freedom, albeit briefly.

IT MAKES US QUESTION HOW FREE WE ARE OUTSIDE

These are memories that are transferred from memory to pen and lived in a way. The author, who returns to those memories years and years later by writing in this book, is always looking for a peace like a tree in which a bird nests peacefully, as in his childhood. On the other hand, there is the story of the years spent in the prison within four walls. On the contrary to the years spent out, this story is the reproduction and questioning of a new reality period based on sadness, pain, impossibilities, longings and hopes rather than happiness, from the memory and imagination of the author, through poetry and thought with limited possibilities. This process includes 8 poetry books written in prison, easier said than done. In this process, while reading the book, we witness that the author’s autobiographical writing language quite takes its share from his poetry. The poet can never give up his poetry. We see this very well in the descriptions in the book. This poetic language takes the book out of its autobiographical character from time to time, taking it to a higher level. The author has preserved its measure, with very balanced outputs, without ignoring the narrative feature of the book, and has provided the reader with a poetic pleasure as well. Another aspect of the book is the fact that in this poetic adventure, the not-lived experiences that are cooked almost like the rituals of a folk poet turn into a wisdom of life with the power and energy of memory and imagination. In this respect, the book passes from its autobiographical feature to a philosophical dimension besides being poetic. The intellectual act of a writer or poet is reflected in the language, this also includes an ontological dimension; from this, a linguistic and ontological act arises indirectly. İlhan Sami Çomak has also become a worry and wounds to many people in the society for years and strives to show us a way out in the labyrinths of our minds on the bleeding and not encrusting concepts of Justice, Death, Time, Love, Humanity, Hope, Despair, Conscience, Anger, Pain, etc. But he does not do this by conscious effort; he does this because he is also looking for this exit with us, but he questions this with a mastery and wisdom from the level of consciousness he has reached, and tries to reach conclusions. Here, at the same time, there is an examination of emotions, the way of philosophy and wisdom. This is an situation that should be appreciated. He himself expresses it as follows: “Still, I must seek wisdom, wisdom through poetry.” This book is openning a new door to autobiographical literature by adding first the poetic dimension, and then the philosophical and intellectual dimension to the narrative dimension. All these dimensions appear and disappear from time to time in the book like a grass, flower or sapling that miraculously grows out of a rock, emerges from among memories and experiences gained from experiences, without breaking the autobiographical narrative foundation and without departing from this foundation.

We have mentioned about some concepts; I would like to draw attention to two of them in particular. The first is the concept of “Time”: This concept has been one of the most important and questioned concepts in the intellectual dimension in İlhan Sami Çomak. He has a desire to get rid of the anxiety of the future against time, to struggle with time, to settle with time; at this point, the importance of hope and the desire to question it with wisdom arises. The second is the concept of “Justice”. There is the existence of justice, its weight, its cruelty, the tendency from the justice that doesn’t exist outside to the inner justice. The author seeks the justice within himself, which he cannot find outside, while doing so, he teaches us all a lesson of humanity: “I have forgiven those who tortured me, those who judged me and deprived me of my freedom by giving the same punishment without caring about the truth, and the society that left me alone in the face of evil and increased silence by turning a blind eye to what I went through, I knew how to forgive!” There are lessons that anyone who reads the book can learn from the author’s unintended, guiding wisdom. This is a guide for all of us. Look what İlhan Sami Çomak says in his book: “Maybe the only place where I am satisfied in life is the road! The bustle itself was life, the walking itself, the goal itself! It was very nice to go.” We are talking about a person who has gone even further in prison, within four walls, than those who live freely outside; that is İlhan Sami Çomak. Freedom is an ontological concept, not a physical one. Freedom of consciousness also brings freedom of the soul. Physical and material freedom is limited by money, value judgments, traditions, etc. İlhan turns the concepts upside down by questioning them again. He makes us question again how free we are in our outer life; how we can be on the side of the truth, the humanitarian, the justice, etc. I underlined so many things while reading the book. I took so many notes. Only good books can make you to do this, and these books are usually our bedside books. This book is undoubtedly one of them. In this context, the book achieves its purpose. This book is the first time that İlhan’s voice, which has been ignored for years, meets the public blindingly. It is a book that everyone should read and take lessons from. It is a book that should be read by everyone, from the lowest segment to the highest segment of the society, from the lowest segment to the highest segment of the state. If we want social peace, democracy and justice in this country, we have to do this first, and then correct the wrongs in the society and the state. İlhan Sami Çomak’s book offers us this opportunity once again with all its humanity and light. Will we miss this opportunity? Look what İlhan Sami Çomak says in his book, as if to prove exactly these: “To accept the truths set by the mind and universal values, to acquire a consciousness of change by staying away from arrogance and masculinity and simplifying…” “So the state must be trained tightly, tought a new language. This is what we need. There was a wall and I overcame it, even though it was bruised and battered.” (p.37)

What does being a poet in prison mean to İlhan? I’ve always said this. When I read each of his newly released books and the books released before I met him for the first time, I saw that he has a poetic talent that transcends space. İlhan Sami Çomak’s poetry has a side that pushes and exceeds all the limits of visualizing the imagination that goes beyond poetry. After having read this book, my advice is if you haven’t read it, you should definitely read his poetry books. You will also see that the topics described in this book have parallels with the poems in his books. This thematic approach, which constitutes the concrete side of his poetry, comes from the nature of the poet, his lived years and past memories. That’s why in his poems we find traces of his village, his childhood, his family, the nature, love, rebellion, women, mother’s love. “Seeking a guarantor for troubles! It is poetry that will do this best,” says the poet. It is said that Poem heals. Real poetry rehabilitate the soul, the body, and the mind; domesticate; humanizes; glorifies; gives consciousness; gives wisdom. İlhan is a poet who knows how to see and benefit from this blessing. Here we are talking about a “new time transformed in terms of space” created by poetry in prison. He himself expresses this time as follows: “General time and time of poetry. The time that poetry creates and organizes, that wants to get rid of the effects of space.” Of course, this is necessary because the poet has been involuntarily removed from the spatiality of real life, and the spatiality given to him inside is very, very limited. In this context, his poetic language has to create the language of spatiality from imagination. The instinct of visualization and imagination in this, too, come to the fore, proceed from the concrete spatial reality of memory and memories, recreate it by diversifying. It is an effort to liberate from time in life, time in prison, from general time proceeding to the time of poetry. Thus, the poet creates a new reality space in his poetry. In this context, spatiality can be rethought with the concepts of space in prison, space in life (in memories), general space and space in poetry. İlhan Sami Çomak gives every poet the chance to look at poetry from a different perspective with his thoughts on poetry; implies this to our consciousness. “Apart from that, in my opinion, the path to be walked for all poets is more or less similar. The important thing is to find the way and know how to walk decisively. Touching the poem is changing yourself, becoming like the poem you wrote by allowing it to touch you, …” (p.92). He is always questioning. He also questions in the poem. While questioning the future of his own poetry, he also expresses the importance of self-confidence in poetry and other poets. Of course, this self-confidence comes from hard work: “I am both a good student and I try to be a part of that big word in terms of adding a word to the poem that was said before me and carrying it to the future” (p.95).