TANER TAN

As soon as the director presses the record button, the image becomes archive. Like memory, the camera re-knits the past through the moment it is in, creating contexts using various universes of meanings. Documentary is one of the fields that makes the necessity of the archive felt the most. It is the most important genre of the discourse of truth in cinema, but it is also the part most affected by the threatening atmosphere because of its role in the truth discourse. In what context, what kind of effects does this threatening atmosphere leaves on the documentary movies. And as a result of this atmosphere what kind of meaning is attributed to the documentary movies?

My main purpose in writing this article is to deal with the topics of documentary cinema, the Kurdish issue and censorship; starting with the end of peace initiative process, that is the year 2015, and to present an assessment of the intersections of these topics. In other words, to describe the story of how the documentaries that could be screened during the peace initiative process became the ‘victims’ of the political atmosphere after 2015 due to the censorship they were subjected to, and how they still ‘stand up to’ despite the hardening political atmosphere.

In 2009, a process called the Kurdish Peace Initiative was officially started by the Justice and Development Party. This was a historical step because official efforts were being carried out for the solution of the Kurdish issue, which can be considered as a milestone for being a democratic country, and the invalidity of state policies regarding conflicts was officially accepted. Right after the peace initiative process started, the reforms enabling the teaching of the Kurdish language were announced and a television channel broadcasting in Kurdish called TRT-6 was opened. Discussions about the initiative frequently took place in the parliament, among the public, and in the media. Extraordinary days were being experienced in Turkey; problems that could not be talked about before began to be discussed throughout the country. With all its ups and downs, the process had become a common issue for all people in society. Because a problem as old as the establishment of the Republic of Turkey was brought to the agenda and a multi-actor consensus area was being tried to be established.

However, in 2015, the process began to rewind irreversibly, with the suspicious death of two police officers in Ceylanpınar, Urfa. The process, which started in2009 and continued until 2015, was interrupted partly, sometimes blocked, and sometimes it was tried to be continued with alternative routes. When all these are taken into account, the atmosphere of peace and tranquility achieved relatively left its place to a chaotic situation. So, how did documentary cinema interact with the political atmosphere during this tense and uncertain period? How was documentary cinema positioned in this changing political climate?

When we look at the quantity of documentaries based on the Kurdish issue in Turkey, it is quite possible to talk about the quantitative increase in documentary films from the beginning of the 2000s to the present, either due to technological, professional or political factors. The fact that especially in the films produced after the 2000s discussed the topics that could not find a place in the public sphere before, and these documentaries convey historical events, shows that the documentaries function as a memory site. Of course, the documentaries shot during this period are not only about the “others” of the society, but also there are also documentaries based on the views of the official ideology. In other words, the official ideology was using the ‘propagandative’ effect historically attributed to documentaries for its own purposes. At this point, it can be said that some documentaries form ‘counter-history’ by getting outside the official discourse, while it is a fact of documentary cinema in Turkey that some of them function as a continuation of official history. Therefore, documentary cinema, which has become a venue for the voices of others in Turkey, turns into a medium in which the Kurdish question is discussed from different perspectives.

From Piran Baydemir’s movie ‘Fecira’

Close-up: Kurdistan (Yüksel Yavuz, 2007, Germany), Prison No. 5: 1980-84 (Çayan Demirel, 2009), Demsala Dawî: Şewaxan (Last Season Lodens, Kazım Öz, 2010), Du Bisk Por-Keçên Dêrsimê yên Winda (Two Locks of Hair: Missing Daughters of Dersim, Nezahat Gündoğan, 2010), Min Rastî Nivîsand – Deftera Lîceyê (I Wrote the Facts – Lice Book, Ersin Çelik, 2012), Fecîra (Piran Baydemir, 2013) can be listed among the documentaries that took the Kurdish issue as the main narrative structure within the process of peace initiative. Therefore, it can be argued that; the experiences of a “relative” democratization process also made itself felt in the field of documentary cinema. However, even though there was a positive atmosphere in the field of documentary, the problems of the political field and its ups and downs became one of the important factors that determined the fate of documentaries. By the way, I am not implying that documentaries dealing with the Kurdish question were definitely started to be shot in this period, which is the subject of a completely different article, my aim is to present a picture of documentary cinema that coincides with this period or increases depending on the relativity of this period.

Were the documentaries created entirely within a free space, starting from the peace initiative process until 2015? How did the documentaries experience the tensions of this relatively free environment? These questions show that, at some point, tensions within the political sphere directly affect documentary cinema. For example, Close-Up: Kurdistan was screened at the !f Istanbul International Independent Film Festival in 2009, two years after its premiere. However, the title of the movie was changed as Close-Up: Kurds, on the grounds that there might be a problem. Thus, the process was not exactly a promise of freedom, but on the contrary, it did not allow the circle of discourse it established to stretch; the discourse of Kurdistan was still a taboo. Another example is “Compulsory Life” (2009), of which making was supported by the state and directed by Zafer Akturan and Sema Ceylan Cabbaroğlu. The documentary is about the life of a family who leaves their village forcibly and whose story ends by immigrating to Istanbul. The point that made this documentary unique in that period was the closing sentence of the documentary: “Forced migration is a violation of human rights”. On the one hand, censorship made itself evident as “covered” under the guise of the sword of official ideology, and on the other hand, when we looked back with the closing sentence of the documentary Compulsory Life after the peace initiative process was over, we witnessed that many people were exposed to forced migration again. However, the fact that this is the ending sentence of a documentary shot during the peace initiative process shows that when we look back today, human rights are also restructured according to the context. Therefore, if there is censorship, for what and for whom is it? Under what conditions, for what motives? All these, as I will explain below, remain current in documentary cinema as fixed questions with varying answers depending on the spirit of the period.

From Kazım Öz’s movie ‘The Last Season: Lodens’

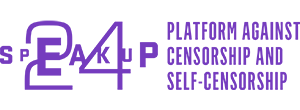

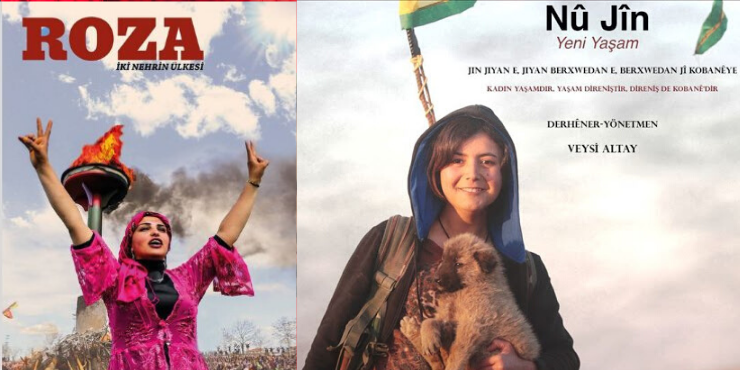

So, what kind of practices did the documentaries, which found a relatively free space during the peace initiative process, encounter after the process was over? What processes did they go through? In this sense, the documentary Nû Jîn (New Life), shot by Veysi Altay in 2015, and Roza – The Land of Two Rivers (2015), directed by Kutbettin Cebe, can be considered as prominent censorship cases of the period. If we summarize Nû Jîn briefly, the film deals with the daily life of three YPJ women, Viyan Peyman, Elif Kobanê and Arjin, during the Kobanê city war in Kobanê, which Altay witnessed in person. The film was watched by approximately one hundred thousand people in many places. After its screening in Istanbul Şişli City Center, the police intervened with gas to the crowd of approximately 1500 people who came to watch the movie. Likewise, a similar picture occurred after its screening in Diyarbakır. Later, the posters that were hung with the permission of the municipality during the screening of the movie at the Yılmaz Güney Cinema Hall in Batman were seized while the movie was being screened. As a result, the manager of the cinema, Dicle Anter, was sentenced to 2 years and 1 month, and Veysi Altay to 2 years and 6 months in prison. Regarding this situation, Veysi Altay states that most of the images he uses in his films are already images used by the mainstream media, and that this is a political punishment. Again, while he considers the peace initiative process as a “trap” in general, he states that the process is a one-way construction by the government in line with the wishes of the government, with the words “You will talk like me, you will think like me”. Therefore, he states that the process has a “regulatory” function on people. In a sense, this situation coincides with a point underlined by today’s censorship discussions; censorship is not only a vertical network of relations between a hegemonic power in the rough sense and the opposing subject, on the contrary, it is an invisible, interiorized organizer. In other words, it indicates the existence of an ideological and constructive censorship, about which Altay mentioned. When Altay answers a question about what kind of a motivation there was behind this censorship case. His words “Works like mine will be a means of confrontation after a while” exposes what censorship aims: amnesia.

Another example is the movie Roza – The Land of Two Rivers. The documentary generally highlights the unity of people constituted of Kurds, Arabs and Assyrians during the war against ISIS. Expressing that the censorship story of the documentary is a ‘discovery’, the director Kutbettin Cebe describes the process as follows: “I received an invitation from the Other Worlds Film Festival (Festival des Autres Mondes) in France. I applied to the French Consulate for a visa to attend the festival. This application appeared on the records of the government, and our state questioned why this director go abroad and caught a ‘criminal’ years after the crime… I was taken to court and as a result, I was released with judicial control and ne exeat .” In addition, Cebe emphasizes that the discourse within the official ideology has changed cyclically, by saying that “who was not marginalized yesterday, was marginalized today”. Similarly, Cebe, who describes the cinema that he tries to make through documentaries as “entrusting the cinema to the space of memory”, says that censorship is on the side of the truths of official discourse and against singular truths.

During these 11 years, where exactly do the censorship mechanisms correspond in terms of documentary cinema, what is excluded from or allowed in the public sphere? It seems meaningful to discuss what documentary cinema conveys to us through censorship, since documentary cinema reminds us that what is left out as much as what is spoken, opens up a space to see from the window of the ‘other.’ Godard’s statement “cinema should make history visible”, when asked the question of whose history should be visible, finds its answer in Walter Benjamin’s statement “to comb the feathers of history backwards”, in my opinion. When it comes to the Kurdish issue and censorship, documentary movie makers turn the documentary into a multi-historical tool in the field of cinema, by combing the history backwards, emphasizing the ‘invisible’, ‘excluded’ and ‘covered’. Thus, censored documentaries have a value in the rewriting of ‘histories’ in the feathers of ‘history’. Having mentioned all these, the events held about the censored documentaries in Turkey, the solidarity networks established with the directors create a shared memory, quite the contrary to the amnesia mechanisms established by the censorship. The fact that memory is a collective existence mechanism, and that there can be no memory without it, causes us to carry the negative effect of censorship to a positive space through solidarity, by coming together and speaking out. This does not mean that all censorship cases leads to establishment of a positive condition, on the contrary, censorship triggers amnesia with all its reality at the point where there is no solidarity.

Utilized resources:

Candan, Can. (Ed.), 2016, Kurdish Documentary Cinema in Turkey: The Politics and Aesthetics of Identity and Resistance. Cambridge Scholars Publishing

Altyazı Fasikül (Fırat Yücel), Subtitle Cinema Association, http://fasikul.altyazi.net/2019/07/03/gelecege-donuk-filmler/ , (15.03.2020).

Altyazı Fasikül (Fırat Yücel), Subtitle Cinema Association, http://fasikul.altyazi.net/2020/01/06/alternatif-hafiza-yaratmak/ , (15.03.2020).