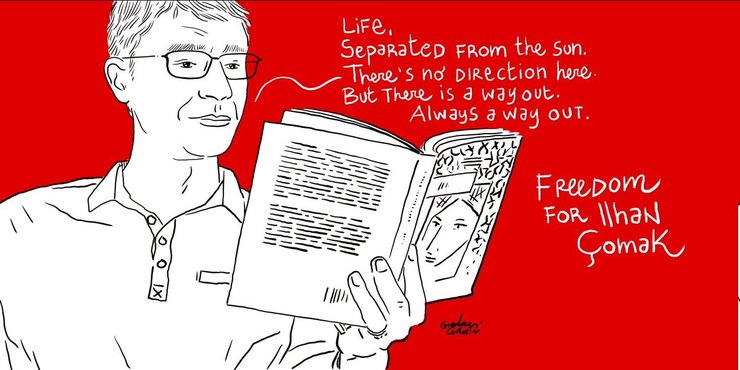

* The drawing belongs to Italian cartoonist-activist Gianluca Constantini.

FIRAT AYDINKAYA

‘‘There is something rotten in the law’’, observes Walter Benjamin in his seminal work ‘‘Critique of Violence’’, as he urges the modern reader to look at the relationship between the law and violence. Benjamin, with this deeply significant observation, leaves us face to face with this inevitable rottenness. Indeed, there is something rotten in the Turkish legal system in recent years. And, the case of İlhan Çomak lay at the foundation of this pandemic of rottenness. There has never been a case which demonstrates that rottenness so clearly. Yet, we have insisted on looking away from both that rottenness and İlhan’s case.

Every small piece of İlhan Çomak’s case, which has been going on a staggering quarter century since July 1994, has laid bare the injustices of the Turkish legal system day after day, month after month, and year after year. İlhan, who was a 20-year-old university student when he went to prison, is now 46 years old. Unfortunately, the rottenness in the law is not contained within courthouses, as it stymies the path of a young person and leaves him face to face with a distinct form of violence: prison.

WHAT IS İLHAN ÇOMAK ACCUSED OF?

İlhan Çomak was (is) accused of violating the most severe article of the Penal Code: “Separating a part of a territory that is under the sovereignty of the state from the state administration’’. Below is the exact wording of the harshest article of the Turkish Penal Code which goes under the following title: ‘Disrupting the Unity and Integrity of the State’.

“ARTICLE 302. – “(1) Any person who commits an act to place all, or part, of the territory of the State under the sovereignty of a foreign state or to disrupt the unity of the State or to separate part of the territory under the sovereignty of the State from the State administration or to weaken the independence of the State shall be sentenced to a penalty of aggravated life imprisonment.

(2) Where any other offences are committed during the commission of this offence, then the relevant provisions relating to the penalties of such offences shall apply additionally.

(3) Legal entities shall be subject to security measures specific to them for the commission of the offences defined in this article.”

The gravity of this situation will reveal itself if one remembers that before the introduction of aggravated life imprisonment into the Code, the former version of the article (art. 125 of former TCC) included ‘‘death penalty’’. If the former Turkish Penal Code were still applicable and the death penalty were implemented, İlhan would be sentenced to death and executed under article 125 of the Penal Code.

Therefore, what İlhan has been subjected to is, in fact, in a way, a psychological ‘‘death row’’ and constant torture. In fact, this definition is a unique form of psychological violence inmates awaiting execution are subjected to. It is thus an existential syndrome. While İlhan has been suffering the syndrome of never-ending imprisonment for a quarter of a century have the allegations against him been proven? Because, looking at the existing picture, one would expect (would have expected) to see firm, compelling, and scientific evidence that leaves no room for doubt proving that he took a gun or a bomb and killed one or more people like a serial killer.

THE TRIAL: LEGACY OF DEMİREL – ÇİLLER – GÜREŞ YEARS

But no! Aside from the idea of him killing someone, dozens of judges, prosecutors, hundreds of police officers who handled the case could not even prove that İlhan ever held a gun. Hypothetical claims, unproven hearsay, scenarios clumsily assembled and finally judicial texts drafted in a Kafkaesque style. This ‘‘fabricated scenario’’, which could not keep someone in prison for even 26 hours in another country, has been keeping İlhan behind bars for 26 years.

Never in his life has İlhan held a gun, nor has he ever killed someone. Let alone separating territory under the sovereignty of the state from the state administration, his feet have not even touched the land on which the prison he has been kept in for a quarter of a century stands. For someone with the spirit of a poet, who arms himself with poetry, his only weapon is his verses. İlhan is a man of letters who is preoccupied with images, verses and constructing words. We are talking about a person who chose to respond to his torturers using literature.

Yes, İlhan is on trial under the harshest article in this country. However, there is not a single shred of evidence in his file that he committed the alleged crime. Excuse me, there is some, if it can be called evidence though. If we count evidence collected through torture and later withdrawn by the two confessors who had given their depositions… This is the legacy of the ’93 concept’ also known as the years when the Demirel-Çiller-Güreş trio considered torture as an ordinary legal instrument. In a way, it is the product of exceptional times when ‘‘the law enforcement created the law’’. A series of ceremonies that the ECtHR found unjust and unlawful from start to finish.

THE CASE HAS BEEN BROUGHT BEFORE ALMOST ALL COURTS

The European Court of Human Rights ruled that the interrogation of İlhan by a military judge, the drafting of investigation documents with the signature of a military judge and his trial by a military judge violated the ‘‘right to an impartial and independent trial’’ under article 6 of the ECHR and that İlhan did not get a fair trial. What the Court in Strasbourg asked of the government with this ruling was to have İlhan retried, this time with a fair trial.

İlhan saw the following courts in chronological order: the State Security Court then the Court of Cassation, the Special Court, Court of Cassation, European Court of Human Rights, once again the Special Court, Court of Cassation, Heavy Penal Court, Court of Cassation and once again Heavy Penal Court and finally the Constitutional Court. Our case has circulated all judges except those in Berlin.

Even the majority of İlhan’s friends whose cases were nearly identical to our case and who stayed in prison for a shorter time period were released. Moreover, in cases dealing with Hezbollah there is no one who stayed in prison for 20 years but İlhan is still behind bars after 26 years. In fact, those who had the same legal status as İlhan and who were released were files that progressed on the path opened by İlhan’s case. In a way, İlhan opened that path, but those who walked on that path are now free while he remains in prison. One need not look at articles or the jurisprudence to understand the legal rationale or the reason for this discrimination. Maybe we should defer to Derrida on this issue: “what could be said about an understanding of ‘justice that goes beyond the law or has no reservations about contradicting it’!”

ECtHR RULES IN FAVOR OF HIS RETRIAL

The European Court of Human Rights, declared the decision that sentenced İlhan to ‘‘aggravated life imprisonment’’ null and void due to the presence of a ‘‘military judge’’ at the time of adjudication, considering this a violation of the right to a fair trial. And it ruled in favor of İlhan’s retrial. The courts resisted in implementing the decision for a staggering 6 years. Following our objection, the appeals court had to accept the request for İlhan’s retrial. Yet, instead of ensuring a retrial that that is line with the spirit of the law, that is, instead of putting material facts up for debate, the ‘‘retrial’’ consisted of reading the old documents at the hearing. While we were expecting İlhan’s release following the decision to have him retried, not much really changed. Once those show trials were over, the panel of judges rendered the same decision once again. To make a long story short, İlhan spent 26 years of his life in prison almost without ever seeing an impartial and independent judge.

Since we started with Benjamin let us conclude with him. If there is something rotten in the law, justice would be the first to be affected from that, humanity would be the next. Yes, İlhan’s quarter of a century-long-trial and the unjust treatment he suffered caused all of us except İlhan to become rotten, but we can still stop this rottenness. It is still not too late.