AYŞEN GÜVEN

“I have never self-censored my poetry, neither has my poetry ever been censored; to the contrary, I actually hear that many of the officials here, who are obligated to read my poetry, quite like it.”

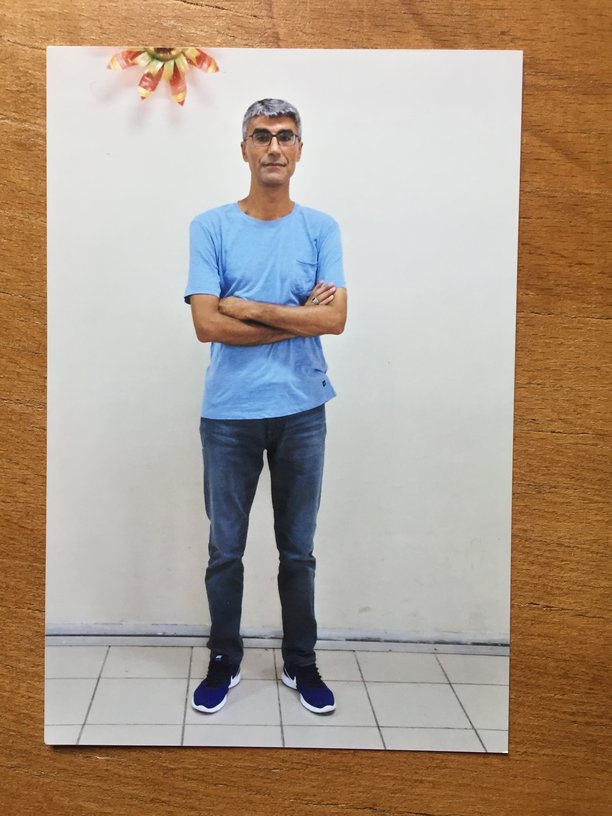

The poet, İlhan Çomak stood trial for 22 years and he has now been in prison for 26 years.. A 2007 ruling from the ECtHR affirmed that he “he did not have a fair trial” and sentenced Turkey to pay the damages to Çomak, who, as he has never committed any offence, has never been proven guilty. He has neither recieved an apology nor had his sentence reversed. His story, in its entirety, is a long and detailed one. I spoke to İlhan Çomak, the poet, about this “never-ending injustice”, about his poems – which are full of life and hold no bitterness despite his confinement, about prison conditions amidst the ongoing pandemic, his health, and about the justice that cannot come soon enough, thanks to the efforts of legal volunteer, İpek Özel, who has taken his case as a “McKenzie friend.”

Çomak writes that the “Feeling of being confined cannot be explained merely by being in prison. The feeling of confinement goes hand in hand with loneliness and the feeling of being forgotten.”

We are only too happy to be part of a growing circle that will ensure the poet is never forgotten.

Let me start by asking about your health. Is everything alright? What do the measures against the pandemic look like in prison?

Thank you so much. I am fine – that is, I am trying to be fine. Aside from my immune system, which has been weakening as I stay away from the outside world, having been in prison for 26 years, I have no health issues for the moment. I am staying in a single cell, and I am already quite meticulous about hygiene and cleanliness.

The prison facility seems to be taking the necessary measures. Our wards have been disinfected; we almost never see the wardens anymore. Letters, packages, and all post arriving from outside are delivered to us after being kept for days to prevent the potential transmission of the virus. Visits had been stopped for weeks, months now; even lawyer’s visits are only allowed in an enclosed system, with limited durations. They say that all of these measures are due to the pandemic. Of course, it is essential to reduce contact, but we already live deprived of any contact. From this point of view, in other words, having to bear with this situation spiritually as well makes our daily lives even drearier, causing our energy levels to drop.

“THE PANDEMIC THREATENS PRISONERS THE MOST”

I am fine, but I am worried for those in crowded wards. Health and hygiene conditions there would not be, could not be, adequate in terms of preventing transmission. Hygiene, nutrition, medical care, communication, ventilation, bedding issues, which had never met minimum standards to begin with, have become all the more important and worrying these days. Nutrition, which is necessary to keep strong, has never been adequate in prisons. I am not only referring to food not being tasty; prison food is neither healthy from a hygiene point of view, nor is it nutritious.

One must admit though, that the Covid-19 disease, which is a great threat for the entire humanity and is referred to as the “global scourge”, threatens the right to life of the people deprived of their freedom in prison more than anyone due to the poor conditions here. I assure you that we all get nervous about the possibility that something might happen to even a single one of our friends who stay in crowded wards, where it is already difficult to maintain good hygiene under normal conditions.

From this point of view, then, could you share with us your own needs and the demands of the other convicts?

There is a crowded group of convicts in the prison, who should not even be here anyway, just like me. More than 300,000 people are said to be in prisons today, with nearly 70,000 of them being essentially political detainees and convicts. Only last year, the government spokespeople announced the construction of 137 new prisons as if it were an accomplishment. It is said that nearly 400 prisons in Turkey are already full.

We are called political prisoners. Most political offenders are persons who have been deprived of their freedom by dishonest trials because they have voiced their opinions and used their democratic rights to criticize. Unfortunately, this is where things stand in Turkey, as they always have. Indeed, we did not have a fair trial, we have been imprisoned unfairly, we do not even know why we are here. If we are to take a look at our cases from a legal point of view there is no lawful explanation for why we are here. So, we should not be here under any circumstances, not only during the pandemic, and with the concerns it raises over the transmission. Most of us have been in prison long enough. I am setting aside my own long-gone youth and my entire life; prison is not a place to stay unfairly for even 26 hours – let alone the 26 years I have spent.

“OUR HEARTS SANK WITH THE EARLY RELEASE LAW”

The new early release law had initially created an expectation of an amnesty; however, it has turned into a disappointment. What is your take on the scope and the consequences of this regulation?

First and foremost, the new regulation on the execution of sentences and early release has been in breach of our existing laws. Our constitution stipulates the equality of everyone before the law. Given that fact, the so-called new regulation does not only lag behind this law, but it also constitutes a violation of the existing law, in other words, of the very constitution. As stated by many jurists specialized in enforcement, execution of sentences serves as “rehabilitation” for a person if the said person is guilty. Punishment cannot serve the purpose of taking revenge, inflicting torture in any country governed by the rule of law, including ours. Furthermore, prisons are not and should not be places planned as places of torment. So, these kinds of lifelong punishments, long-term convictions are in breach of humane law. Above all, releasing only some of the convicts based on a newly issued regulation and not allowing the others benefit from this potentially favorable regulation, not doing justice in terms of enforcement is not acceptable, and creates a flagrant double standard, which constitutes discrimination in law.

Setting aside the injustice I have suffered myself for 26 years, painful experiences I have accumulated within this system, even only based on what we can watch on the TV, the attitude of politicians, and the current government, tell me not to entertain hopes. Indeed, I know what this system’s, this country’s sense of justice means very well as someone whose trial lasted for 22 years – something unprecedented in the global history of law. Yet, what we still wish, and desire for this country is that those who govern us choose a path that is democratic, just, and compliant with the law at least while issuing new regulations, at least from this point onwards. We have no other option than becoming a democratic, pacifist country governed by the principle of the rule of law. However, the law on the execution of sentences and early release, which the parliament passed in its current form, has disappointed us for the moment. It looks like with its practices; Turkey has chosen yet again to stand in breach of law. The hopes now lay in the Constitutional Court’s correcting this particular wrong.

“I HAVE NOT SEEN THE DOCUMENTARY ABOUT ME, NOR HAVE I WATCHED THE VIDEOS MADE OF MY POEMS”

On social media platforms, poets have been making videos where they read out your poems, calling for your release. There are international initiatives for you. For example, Norwegian PEN is running a campaign led by their Turkey Adviser Caroline Stockford where poets from around the world are writing for you. Burhan Sönmez and İpek Özel are also organizing these initiatives; there is a constant solidarity outside, that also maintains contact with you. How does this solidarity look from inside?

Unfortunately, I have never seen any video made about me, or any documentary produced about me; I have no means to watch any video in prison. Yet, I am informed of everything and this solidarity is making me stronger.

Prison is an evil within evils. Indeed, it is a great evil. It clashes against and is in direct contrast with the shortness and preciousness of life. The greatness of the evil comes from that. The feeling of confinement cannot only be explained by being in prison. The sense of confinement goes hand in hand with loneliness and the feeling of being forgotten. The interest the world takes in me, in my poetry, in the struggle for my freedom is precious, so are the gestures of love, interest and intimacy of the people who do not know me personally, the efforts of poet and artist friends who are trying to lend a voice to my poetry, and the efforts of journalist friends who wrote and let people know about the injustices I suffered. I do not have the words to describe how touched I am by all of these efforts; how precious every single effort is to me. I send greetings to each and every one of them. And, thank you for this interview in these days when everything is under quarantine, everything has become quiet.

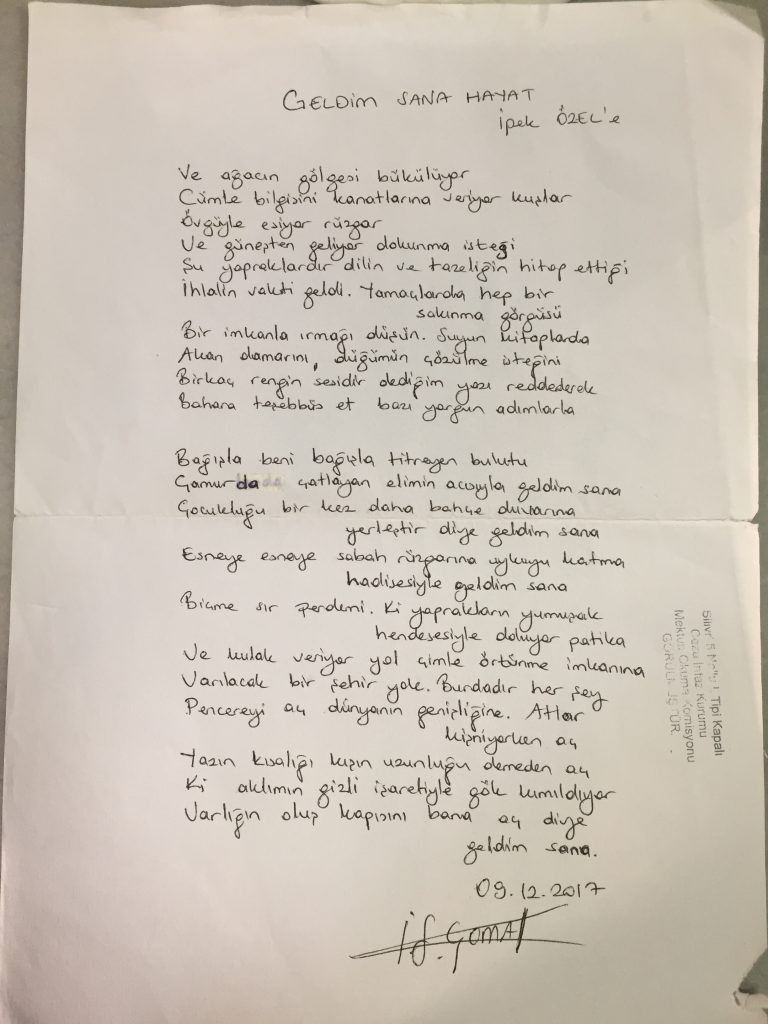

Besides having poets from Turkey and Europe lend their voices to my poetry, and having meetings organized about me as part of the PEN Norway’s programme; yes, there is also work going on to translate my poems. I am aware of the initiatives to have some of my poems translated for publication in magazines in England. I have been filled with joy since I heard that 10 pages were dedicated to my poetry in Trafica Europe in the US, alongside some very well-known writers from Turkey. Similarly, I know that there is a project to translate a selection of my poems in English into a book and I find these initiatives exciting. Not being able to be involved because of my imprisonment strangely increases the load I bear. However, hearing that my poems are being translated into French, German and Spanish will always be an empowering, beautiful surprise to me under any circumstances.

In which year did you write your first poem? Did you read and write poetry before you were sent to prison?

I did not write poems before prison. I wrote my first poem in prison and my first poetry book was published when I was here in prison. I was only 22 years old and a university student before I went into prison. I had quite recently come to Istanbul from Bingöl, and it was my second year at university. Now that I look back, I accumulated poetry inside of me even when I did not write any poems back in those days. I have always read of course, including when I was not writing poetry. I loved literature, not just poetry. I have always worked and I am working today, even at this point, to emulate great poetry and poets, to follow the grace of their poetry, to be both a good “student” by reading, not just writing, and so to become a piece of that great discourse of poetry and literature by adding a word to the poetry that was told before me, and carrying it into the future.

“THE VENUE POETRY IS WRITTEN CAN OVERSHADOW THE POETRY ITSELF”

Yes, in a way, I have become a poet in prison, but I have always thought about it as follows: the venue or imprisonment is important, surely. But what makes the poet speak is not the walls, rather, the moment when the poetry appears within the poet by developing and growing with its own dynamics represents the unattainable, formless, subtle elusiveness of this entire process. I say this because, yes, a link may be found between my being in prison and being a poet, because I was not a poet prior to my imprisonment, I was young, I was a student, I had just come to a big city from Bingöl, and I did not have time to write poetry, so preoccupied was I with the anxiety of being a student. Indeed, it is also possible to think that I might have become a much better poet if I had not been in prison. Joking aside, what I mean to say is that where the poetry is written can overshadow the poetry itself. Many times I have encountered reviews expressing surprise at how come such poetry can be written from a prison. I have welcomed these with joy as they announce the creativity of the poetry proven under any circumstances. Creativity cracks walls; it penetrates at any cost, renews its determination to flow freely! But what is essential is the poetry itself, not where it is written.

“THERE ARE NO COMPUTERS, NOT EVEN A SIMPLE TYPEWRITER”

Besides not being free, are there any practices in prison conditions that prevent you from writing or makes it difficult for you to write?

Ah, how can there not be? Unfortunately, all eight of the poetry books I have written had to be published while I was in prison. Starting from the most technical side of things, we do not have a computer, not even a simple typewriter here. Given the state of affairs, we write everything by hand. I have always written all of my poems, essays, and papers by hand and sent those drafts out by post, which only means that the prison’s letters committee read and supervise what I write before they send them out to the recipient. All of the poems and other texts I have written were typed on a computer outside of the prison, in other words, they have always been edited outside.

When my relatives, who have undertaken the editing, failed to read a simple letter in my handwriting, the edited, typed texts I received, in turn, would naturally be miswritten. The incoming texts would, of course, be delivered to me after having been approved by the committee of letters. If these texts contain errors, which they mostly end up doing so simply because of the way we work, I re-edited them, and they would then go through the same procedures; the poem (or the essay) was sent out, re-edited, redelivered. Just imagine how painstaking it is to write a simple poem one verse after another, to even see the verses as a whole.

“OUTSIDE, YOU CAN CONTROL YOUR OWN TIME, BUT IN PRISON, YOUR TIME IS CONTROLLED”

Given the technical conditions in prison, how motivated do you feel? For example, people in prison are always assumed to have plenty of free time. How does the mind experience it? How does one create?

These works of mine, without a doubt, were created through years of disciplined work. My poems piled up and were published as I kept on writing. You are quite right, people assume, looking from the outside, that those in prison sit around doing nothing, and that they have plenty of time in any case. In fact, this is not true at all. Here, under these circumstances, especially if you are a political prisoner with all eyes on you, and you stay in a high-security prison, it becomes even more challenging to find the specific time to concentrate, to turn into yourself, to create works in a field such as poetry, which requires such an incredible amount of special attention and time. It has long been argued that prison transforms your sense of time. Outside, you can control your time, but inside a prison, your time is controlled by a number of factors beyond your control. This is a factor which makes it challenging to write poetry, concentrate, or work in a disciplined manner.

The core or the truth of the matter is that we must also talk about inspiration when it comes to poetry, the part where you bring the poetry out of you, and this has been transformed by the place and the way it twists and bends our feelings and consciousness, and also how it occupies our emotional and intellectual world to the same extent. As you may be able to tell, prison is not in any way a “poetic” environment that nurtures a person, let alone a poet. So, being a poet in prison requires one, before all else, to persist in making efforts to overcome the conditions one is in. if you are an imprisoned poet, you find yourself having to struggle both in terms of nurturing, taking inspiration, and against this place in which you have been imprisoned, and the confinement of this constricting, talent-, dream- and creativity-obstructing place. In other words, it’s like starting a football match 1-0 down.

“IF YOU ARE IN PRISON, NOT ONLY THE HUMAN BEING BUT ALSO POETRY IS IN ISOLATION”

I suppose there is also an inability to hear the criticism first-hand, and being deprived of witnessing reactions of readers to your work.

Of course, if you are in prison, not only the human being but also the poetry is isolated. Given that, it becomes quite challenging for the poet to find a platform in which to weigh their poetry. Prison creates the obligation for the poet to assume the duty to criticize their poetry, which is supposed to be the duty of others. Without the criticism of others, the poet trying to mold his own poetry by himself almost walks through a forest of uncertainty. I am a believer in criticism. If I was able to communicate with people freely, the criticism of a poet friend might have brought to my attention newer perspectives, helping me achieve a poetry that is different from, and stronger, than what I have today; I have never had that here.

Therefore, being in prison and writing poetry from inside is a trauma in and of itself. Especially considering the 26 year-long relentless journey that has felt interminable, one could even say that being a poet here is a blatant tragedy.

As you have pointed out, you are constantly being monitored, controlled in prison. How about your poetry? Have you ever had a work censored, or have you ever practiced self-censorship to make sure your poems got out unharmed?

No, I have never done anything like that. I have never been a typical “prison poet” in the traditional sense of the word, who writes poetry like a manifesto or an anthem, views the poetry as a political statement, as a discourse, or tries to convey a political message with their poetry as a political prisoner.

It is not right to seek an absolute parallel between being in a dungeon and the poetry written. It is hard for one to speak of oneself, but I will say it anyway: my poetry derives strength from the weight of words; it is the kind of poetry that flows rapidly, running breathlessly towards life outside. I strive to write a cultivated poetry that is not inclined towards pessimism, glorifying pain, or accentuating suffering. I think in terms of images, and essentially I try to build my poetry on the basis of vision. I write a poetry that wants to hear the sound of life without losing a sense of rhythm.

I use poetry as a light to help me to see life better. I write with the touching grief of a life passing by with all its joy and pain, beyond this seized state of mine, beyond another life; in a way, I run after all that I have lost with my poetry! From that viewpoint, what I invite to my cell with my poetry is indeed life. I have never self-censored my poetry, neither has my poetry ever been censored; to the contrary, I actually hear that many of the officials here, who are obligated to read my poetry, quite like it.

“I WANT THIS INTERMINABLE INJUSTICE TO END NOW”

You have been detained for so many years – unjustly so. Don’t you feel any anger at all? Your poems are so full of peace and life that one cannot help but be amazed by the feelings that your verses inspire.

Anger is a very basic and strong feeling in humans. If a person has suffered severe oppression, the resulting anger might be very destructive, growing until it damages the soul and turns into hatred. And, once anger has turned into hatred, it becomes absorbed in itself with a greed that knows no limits, going above and beyond whoever or whatever it was initially directed to, making no distinction as to who is rightful and who is not, what is right or what is wrong, as if it wants to announce its existence by destroying everything in its path. I know from my testimony, that the person who hates is included in the destructive power of their own hatred. Indeed, hatred hits its owner first, missing the intended target in most cases. I have experienced and still am experiencing the deepest, the most severe oppression. Yes, anger has paid me a few visits, but I never let it become a constant feeling. It has been more momentary, functioning as a reflex that alerts me in the face of evil, it has never become permanent, and has definitely not turned into hatred.

No, I do not feel anger, I hold no resentment, no grudge against anyone. I do not come from such a culture, from a breeding that feeds on hatred, revenge. I am Alawi, I was raised in a family that believed in tolerance, forgiveness, understanding, and love for human beings, and not one that believes in hatred and grudges. However, I want this whole episode, this ceaseless injustice which cost me 26 springs, 26 summers, 26 autumns, and 26 winters and which took over my whole life, to be over already.

How do you think “justice” can be served for you from now on?

Justice will surely be served when I am freed as soon as possible, when I no longer have to sleep in this prison – not even another night – when I get to live a simple life with my loved ones, my family, when I do not spend springs inside, when I can be side by side with the people I love, and when we are given an opportunity and allowed to forget our past suffering.

I did not do anything to be pardoned for, I am not in prison because I committed a crime. The mere fact that the ECtHR requested a retrial for me shows that my trial, and this punishment to which I was sentenced, was unjust. The fact that I was once again sentenced to life in prison while my innocence was so obvious during my retrial is simply a repetition of the injustice I suffered. So I do not expect a pardon but a remedy of this injustice, this lawlessness I suffered. I expect the Constitutional Court to rule in my favour and an end to this 26-year-long lawlessness. This is the only way justice can be served.

“I EXPECT THE CC TO REPEAL THE EARLY RESELASE PACKAGE”

What are your expectations about the legal process?

I expect the Constitutional Court to repeal this new early release package in view of the constitutional principle of equality before law. Especially given such risky, unhealthy conditions, the CC cannot and should not turn a blind eye on the creation of inequality by the hand of state. Protecting the right to life is the primary duty of the state regardless of offence, offender, regardless of language, gender, race, ideology, political opinion.

This current law, the re-regulated enforcement regime, is a discriminatory bill that is in complete violation of, first and foremost, our own Constitution, UDHR, UN International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, UN Standard Minimum Rules for the Treatment of Prisoners, ECHR, Law on Enforcement, European Prison Rules, Recommendations of the Committee of Ministers of the Council of Europe, UN Principles of Medical Ethics, and former Constitutional Court rulings on similar subjects. What else can we expect from the judicial process but a remedy of this violation?

Do you have a call you would like to communicate via us for the public opinion and officials?

My trial took exactly 22 years. The courts where I was tried changed names; State Security Courts, Special Authority Courts became courts that were ‘normalised’; those judges and prosecutors who had tried me have since been arrested and convicted of being ‘terrorists’, ‘coup-plotters’; still, I have remained in prison. I am a poet, I have already poured out all that has passed through my mindand my consciousness for 26 years into my poetry. I do not deserve this ‘relentless evil’ that I have suffered and that has been ongoing for 26 years. I want this cruelty, this lawlessness to come to an end already.

THE JUDICIAL PROCESS: WHAT HAPPENED?

İlhan Çomak was taken into custody by the police in 1994 when he was a 21-year-old student at the Geography Department of the Science-Literature Faculty of Istanbul University. Following sixteen excruciating, torture-filled days of detention, he was arrested by the State Security Court for “undertaking separatist activity” and placed into Bayrampaşa Penitentiary in Istanbul. Çomak was sentenced to life in prison in 2000 as a result of the trial held by the SSC based on the records of a statement issued by the police through torture, without any concrete evidence. After the Court of Cassation’s approval of the judgment, the case was appealed at the ECtHR.

In 2007, the ECtHR ruled that İlhan Çomak did not have a “fair trial”, sentenced Turkey to pay damages and ruled in favour of Çomak’s retrial.

The application of his lawyer based on the requirement to implement provisions of the new Criminal Code, issued in 2005, which are legally in his favour, were rejected by the local court; however, Çomak’s case was reversed by the Court of Cassation on the basis of the procedure. Yet, in January 2013 the court of first instance renewed the previous ruling despite the Court of Cassation’s decision to reverse it, and the case was resubmitted to the Court of Cassation.

The 4th Judiciary Package, issued in April 2013, paved the way to retrial for 220 cases, which were brought before the Committee of Ministers of the Council of Europe. The application of Çomak, based on this ruling in his favour, was also rejected despite the new law. Fortunately, a higher court admitted the application, and Çomak appeared before the Special Authority Court No. 9 for the first hearing in Istanbul, on 19 December. This court, too, rejected İlhan Çomak’s request to be released and the next hearing was scheduled for 11 March 2014.

Because of the rejection of his request for release by the local court, the lawyers filed an application at the Constitutional Court on 6 February 2014, based on lack of legal impediment before İlhan Çomak’s release, pending trial.

The hearing, which was postponed to 11 March, was rescheduled, this time due to the abolition of Special Authority Courts. The petition requesting the release of Çomak, which was filed on 8 May 2014 by the lawyers to the Court on Duty, resulted in yet another rejection by the 4th High Criminal Court of Istanbul of the petition to release İlhan Çomak pending trial.

The trial had finally begun with the hearing which was postponed to 5 September 2014; however, this time the court ruled to return the case to the High Criminal Court No. 9, which was the previous court handling the case. The High Criminal Court No. 9, in its turn, submitted the case to the Court of Cassation based on lack of jurisdiction. The Court of Cassation eventually ruled that the High Criminal Court No. 4 should review the case.

After years and years of waiting, Çomak finally had another hearing on 02.07.2015; however, this time the court postponed the hearing another six months, or to 22 December 2015, because his actual case file was not received, thus could not be reviewed. The hearing that was rescheduled to take place on 22 December 2015 was once again postponed to 12 April 2016, based on the same justification.

Finally, hearings started on 12 April 2016, or 8 years after the ECtHR ruling in favour of İlhan Çomak’s request of a retrial. Nevertheless, İlhan’s request to be released pending trial was rejected once more even though he had been imprisoned for 20 years. The courts still did not release Çomak after any of the hearings which started on 12 April 2016.

Not much has changed within the 22 years since his first trial at the State Security Court, and the court continued to consider the former ruling, which was not found fair by the ECtHR due to the presence of the military judge, valid and approved. In any case, the court indeed failed to abide by the previous ruling of the ECtHR by not ruling to release Çomak in the first place, and “repeated the trial” instead of doing a “retrial”. In other words, the court insisted on considering the previous judgment valid, abolishing, in effect, the ruling in favour of the retrial. As a matter of fact, the logic was clear: if Çomak had been convicted, how come he was retried? and if he was detained, how come, and based on which law someone who had been in prison for more than 21 years could remain a detainee.

İlhan Çomak, who represents a first in the history of law in Turkey and in the world and who has been jailed pending trial for twenty-two years and kept in prison for twenty-six years, was sentenced to Life in Prison in this process. The Court of Appeal immediately approved the judgment and in April 2018, the Appellate Court (Court of Cassation) reapproved the judgment; the case is now pending at the Constitutional Court. It will then be resubmitted to the ECtHR.

A documentary on the life of the poet İlhan Çomak and the injustices he has suffered can be found here:

Directors: Çiğdem Mazlum, Sertaç Yıldız

Voiceover: Muhammet Uzuner

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8y28eaQOh-w